Contents

Introduction

Early in the 20th century, the remarkable discovery was made that light could behave as a particle and that particles such as electrons could behave as waves. This flipped the traditional conceptualisation of these entities on its head, revealing that they had a dual nature and could behave as particles or waves depending on their circumstances.

In this post, we’re going to explore the quantum mechanical phenomenon of wave-particle duality and review the evidence that supports it.

Let’s begin!

What is wave-particle duality?

Wave-particle duality is the concept that waves can behave as particles and particles can behave as waves, depending on the experimental circumstances.

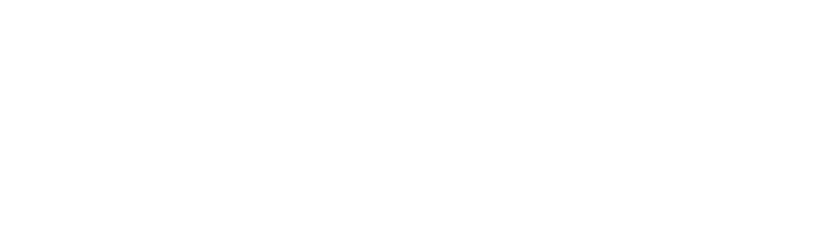

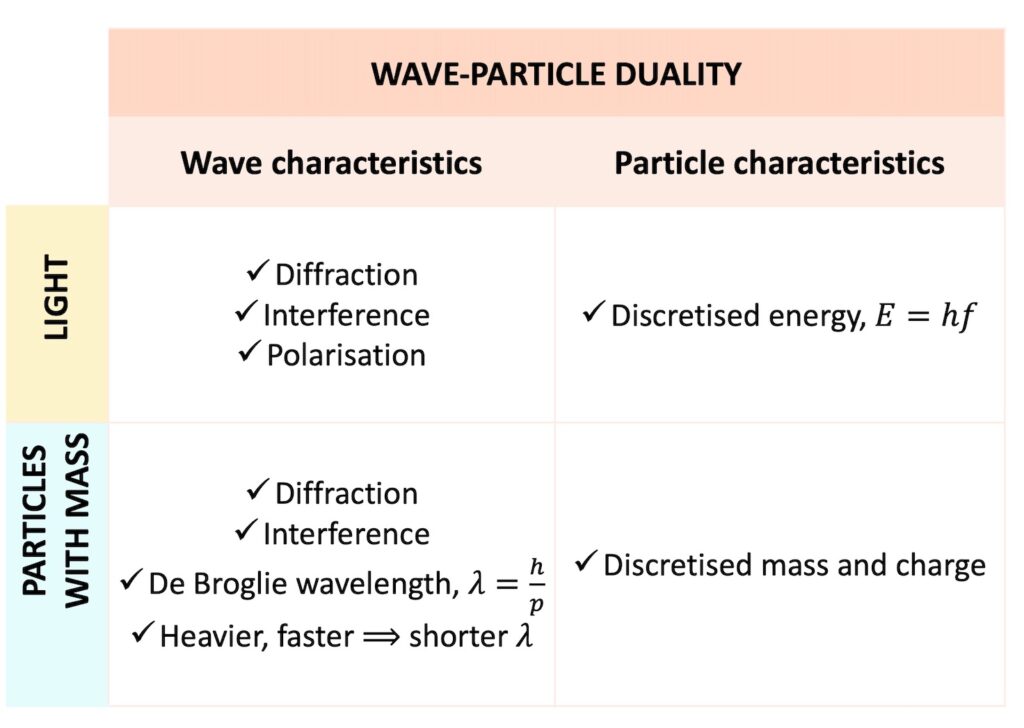

Thus, we can observe a single entity displaying wave characteristics such as diffraction, interference and polarisation at one time and particle characteristics such as a fixed mass and a fixed charge at another time.

Having a fixed, discrete amount of a property is sometimes referred to as the discretisation of a property. We can say that an entity has discretised mass and charge, or discretised energy.

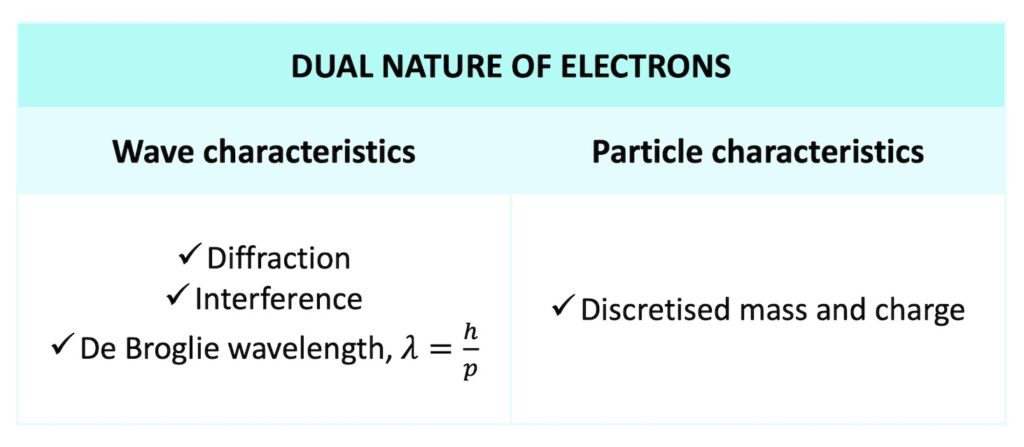

Thus, entities with wave-particle duality display both wave characteristics and particle characteristics as follows:

The dual nature of light

Before the early 20th century, light was thought of as a classical wave. It could be shown to diffract and interfere, but there was one experiment that could not be explained by classical wave theory.

In this experiment, light was shone on a metal surface and it gave electrons in the metallic lattice some energy to escape. Surprisingly, electrons were only liberated if the light’s frequency was at least equal to a minimum threshold. This is called the photoelectric effect.

It did not make sense with classical wave theory. If light were purely a wave, then even with low frequencies it should be possible to liberate the electrons by using a high enough intensity or by shining the light for a long time and waiting for the energy to accumulate. But this did not work.

To explain this, Einstein proposed in 1905 that light arrived in discrete packets of energy. These discrete packets (called photons) are absorbed by electrons on a one-to-one basis, so if the photon has enough energy the electron can escape, and if it doesn’t the electron can’t.

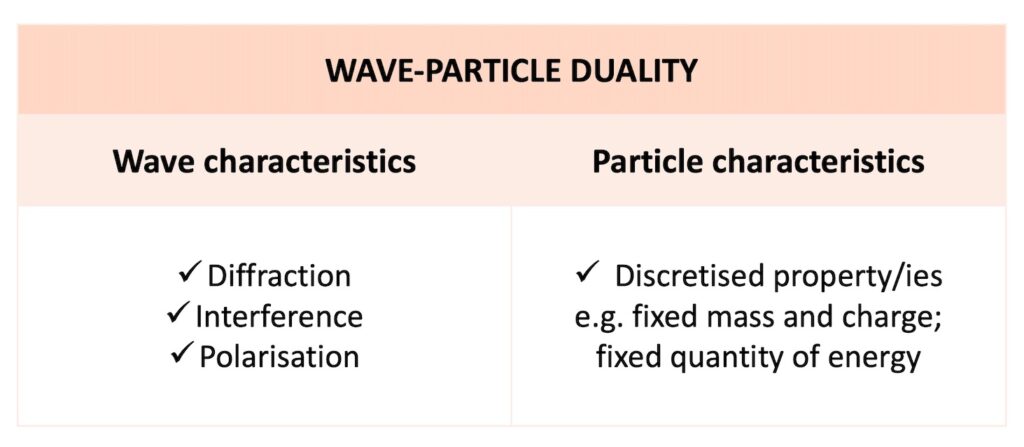

The amount of energy carried by each photon is give by Einstein’s equation \(E=hf\), where \(h\) is Plank’s constant and \(f\) is the frequency of the light!

As well as having wave properties, light therefore also has particle characteristics by virtue of its discretised energy.

The dual nature of electrons

In 1924, the French physicist Louis de Broglie made a radical suggestion that particles such as electrons could behave like waves. He proposed that a particle with mass could have a wavelength that was inversely proportional to its momentum:

\(\lambda=\frac{h}{p}\)

The de Broglie wavelength was confirmed experimentally five years later by electron diffraction experiments.

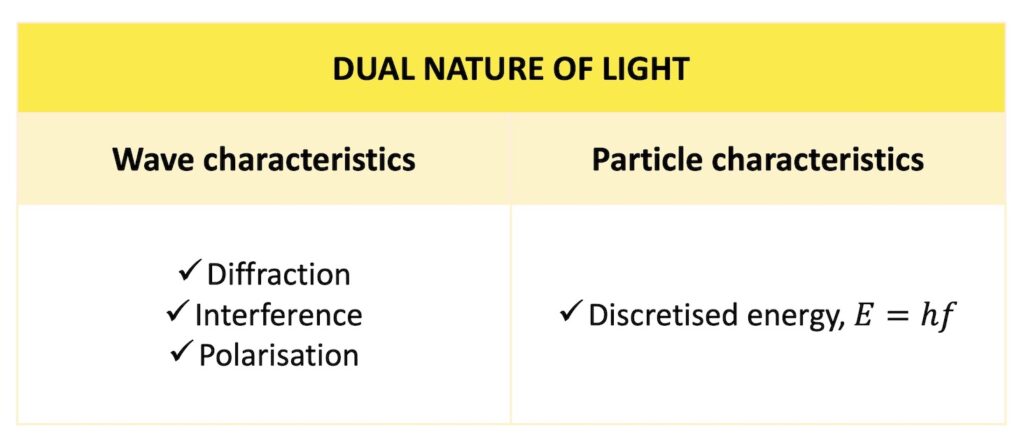

The basic setup is to accelerate electrons towards a crystal lattice which acts as a diffraction grating and detect the diffraction pattern on a screen.

This experiment elegantly demonstrates both types of behaviour of electrons. When they are accelerated in an electric field towards the grating, they exhibit their particle characteristics of fixed mass and fixed charge. When they diffract through the grating, they exhibit their wave characteristics and de Broglie wavelength. When they are detected at the screen, they exhibit their particle nature again by arriving at discrete locations.

Since \(p=mv\), the faster the electrons travel, the shorter their wavelength. By adjusting the speed to which the electrons are accelerated, their de Broglie wavelength can be tuned to be approximately equal to the grating spacing so that diffraction can take place.

In summary, electrons have wave characteristics thanks to their de Broglie wavelength and particle characteristics thanks to their discrete mass and charge.

Wave nature of massive objects

We can expand this dual nature to other massive objects, not just electrons. Let’s look at some examples!

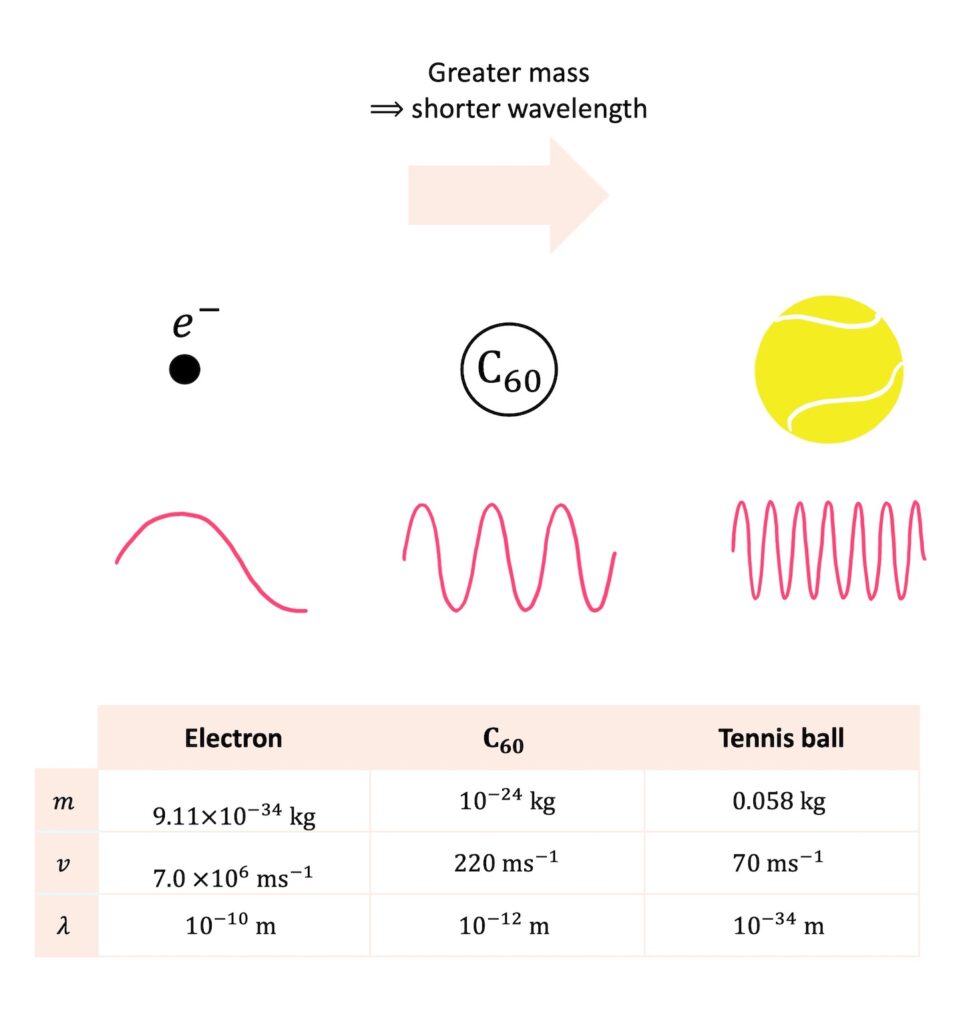

Since the de Broglie wavelength is \(\lambda=\frac{h}{p}=\frac{h}{mv}\), the greater an object’s mass, the shorter its wavelength. For example, an electron travelling at a speed of \(7.0\times 10^6\,\rm{ms^{-1}}\) has a de Broglie wavelength on the order of \(10^{-10}\,\rm{m}\). Meanwhile, a \(\rm{C}_{60}\) molecule (made of 60 carbon atoms) travelling at \(220\,\rm{ms^{-1}}\) has a wavelength on the order of \(10^{-12}\,\rm{m}\). Despite being slower, the heavy molecule has a much shorter wavelength than the tiny electron.

The wave nature of \(\rm{C}_{60}\) was demonstrated experimentally in a groundbreaking experiment in 1999. Although experimentally challenging, \(\rm{C}_{60}\) was shown to diffract through a crystal lattice, just like electrons. This provided powerful confirmation that wave-particle duality applies not only to subatomic particles, but also to significantly heavier objects.

What about a tennis ball?! A tennis ball travelling at \(70\,\rm{ms^{-1}}\) has a de Broglie wavelength on the order of \(10^{-34}\,\rm{m}\). This is absolutely minuscule! For comparison, the diameter of the nucleus of an atom is approximately \(10^{-15}\,\rm{m}\), so the tennis ball’s wavelength is \(10^{19}\) times smaller than the atomic nucleus.

The tennis ball’s wavelength is so small that there is nothing in the universe small enough for it to diffract through! As a result, we do not observe the wave-like characteristics of tennis balls and we only see them behaving as classical particles.

Summary

Here’s a handy summary of the key principles we’ve covered:

Conclusion

I hope you’ve enjoyed this review of wave-particle duality! We’ve explored the quantum mechanical principle of how light and massive particles can have both wave and particle characteristics.

With these insights, you might enjoy taking a deeper dive into the fascinating topics of the photoelectric effect and electron diffraction.

Happy studying!